-

Central bank eased monetary policy despite inflation pressure

-

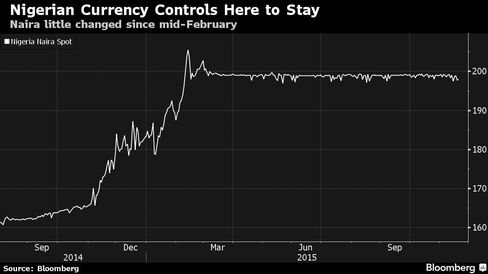

Governor keeps foreign-exchange restrictions in place

Emefiele, 54, reduced the benchmark interest rate by 2 percentage points to

11 percent on Tuesday and lowered the cash reserve ratio to 20 percent to help support an economy struggling to cope with falling oil revenue. With importers blocked from accessing dollars, the liquidity boost may do little to increase output in manufacturing and other industries, while fueling inflation.

“It is difficult to overstate the degree to which this is a highly unorthodox move,” John Ashbourne, Africa economist at Capital Economics in London, said in a note to clients. “Nigeria faces high inflation, pressure on its currency, and it desperately needs to attract foreign capital to fund the current account deficit created by low oil prices. It is, in short, in exactly the sort of situation in which economists would generally expect – and recommend – tighter monetary policy.”

“It’s hard to see this set of policies succeeding in the long run,” Charles Robertson, chief economist at Renaissance Capital Ltd., said by phone from London. “These are policy choices that have a finite lifespan. Unless Nigeria is saved by a much higher oil price, it is going to carry a lot of costs for the economy.”

Monetary policy easing signals the central bank has no intention of devaluing the naira yet, according to Razia Khan, head of Africa economic research at Standard Chartered Plc in London.

Weak Economy

Emefiele cited weak growth as a reason for reducing interest rates. The economy, the largest in Africa, expanded 2.8 percent in the third quarter from a year earlier, slightly higher than the 2.4 percent recorded in the previous month and less than half the 6.3 percent expansion in 2014.“At the last meeting, we said that we had attained the end of tightening and that there was a need for the central bank of Nigeria to be seen to play its own role to put in place policies and regulations that will stimulate growth and development in the country,” Emefiele said.

Lower interest rates may add to pressure on inflation, which slowed for the first time in almost a year in October to 9.3 percent. The central bank’s goal is to keep inflation in a range of 6 percent to 9 percent.

“There is a trade off,” Lanre Buluro, head of research at Primera Africa Securities Ltd., said by phone from Lagos. “In the short term, the central bank wants to trade off inflation and if the economy picks up it will tighten again.”

No comments:

Post a Comment